Mandatory Religious Taxes: A Pillar of Social Welfare Across Faiths

Religious communities throughout history have implemented practices to support their members and social welfare. One such practice is the concept of a mandatory religious tax. This article explores this concept, focusing on Islam and exploring similar practices in other religions.

Zakat and Khums: Pillars of Islamic Finance

Islam has two primary mandatory religious taxes: Zakat and Khums. Both contribute significantly to Islamic finance and social structures.

- Zakat: This annual tax requires Muslims to donate 2.5% of their wealth that has been held for a lunar year. This purifies wealth and supports those in need, such as the poor, the indebted, and recent converts.

- Khums: This tax applies to specific types of wealth, like business profits or agricultural produce. Muslims pay one-fifth of their surplus income after expenses and debts. Khums is distributed according to Islamic law, with a portion going to religious authorities and the remainder to the underprivileged.

Beyond Islam: Tithing and Tzedakah

While Zakat and Khums are central to Islam, other religions have similar practices:

- Judaism: Tzedakah is a mandatory obligation to donate a portion of income to charity. The specific amount is not fixed, encouraging generosity based on individual circumstances.

- Christianity: Tithing, the practice of donating 10% of one’s income to the church, is a concept found in some Christian denominations. While not universally mandatory, it remains a significant aspect of Christian stewardship.

Shared Goals: Social Justice and Divine Favor

These mandatory religious taxes share common goals:

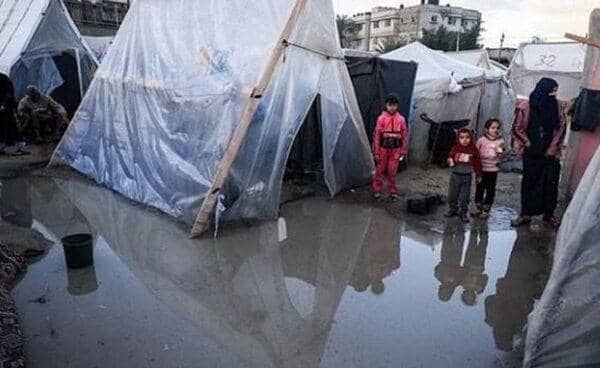

- Social Welfare: They provide financial resources to support the less fortunate within the religious community.

- Fair Distribution of Wealth: These practices aim to ensure a fairer distribution of wealth within society.

- Religious Duty and Divine Favor: Fulfilling these obligations is considered an act of worship and a way to gain favor with God.

A Universal Commitment to Community

The concept of a mandatory religious tax transcends specific religions. It reflects a universal belief in the importance of social responsibility and supporting those in need. By contributing a portion of their wealth, believers promote a more just and equitable society, fulfilling a religious duty and strengthening their faith.